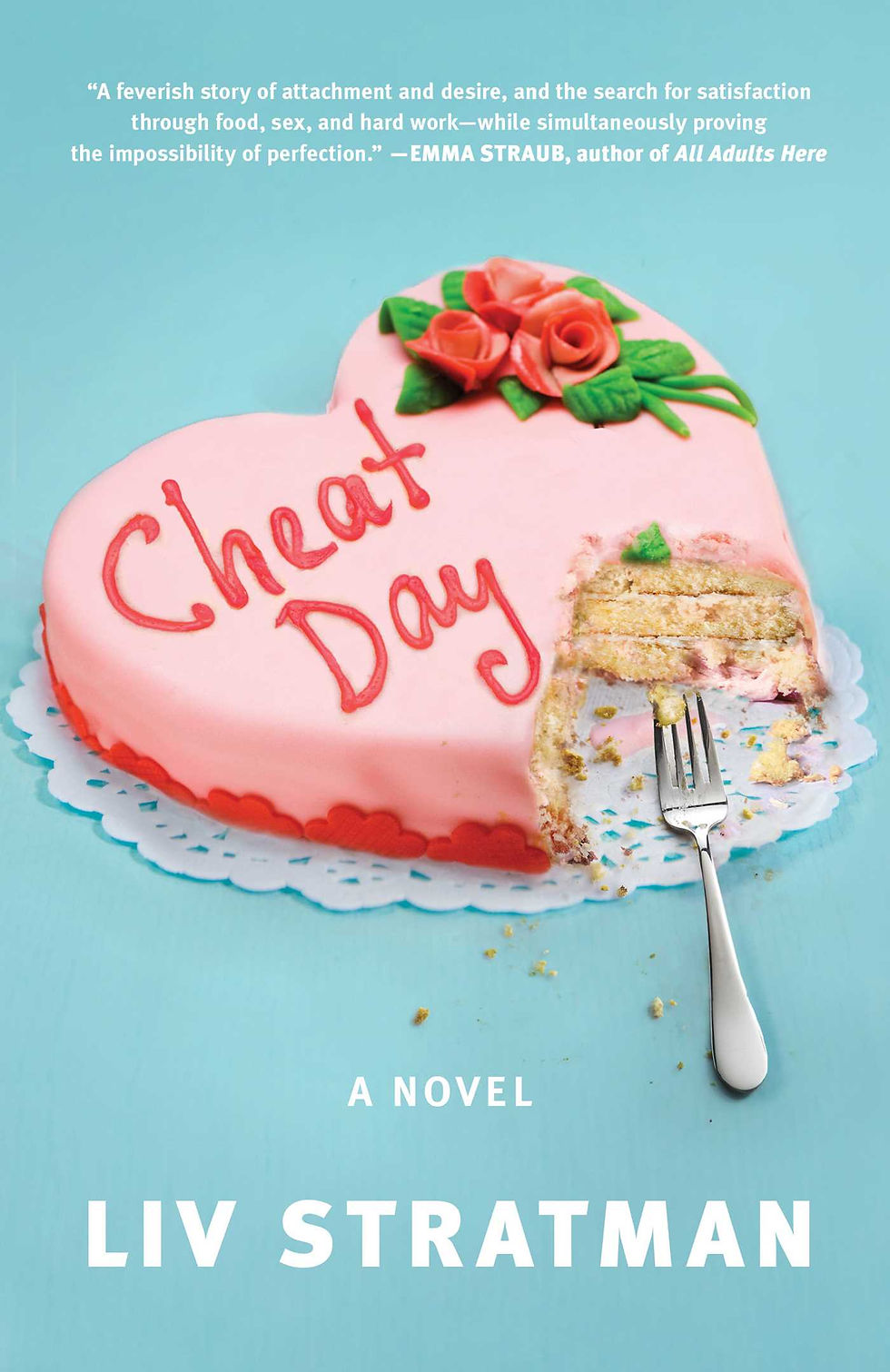

Cheat Day by Liv Stratman

- Mel Ann Rosenthal

- Nov 8, 2021

- 9 min read

Updated: Nov 9, 2021

Dieting is, regardless of any potential health benefits, a business. Worth an estimated $71 billion, it targets the insecurities in us all. Matt Haig gets right to it in Notes on a Nervous Planet, dissecting our self-image, which pinpoints one reason of many why we humans have become more anxious and depressed over time. He says, “Never in human history have so many products and services been available to make ourselves achieve the goal of looking more young and attractive.”

With recent articles like “Is B.M.I. a Scam?” in the New York Times, The Guardian’s “Weight loss ‘before and after’ photos don’t give us the full picture of our health,” and, in The Washington Post last year, “Why making your diet part of your identity is bad for your health - and society,” it feels like the media is starting to focus on a fuller picture of our whole selves, bodies, and minds. While there are many blips (see Instagram’s apology for wrongfully targeting users with eating disorders; though for what it’s worth they have for some time been working toward limiting posts and hashtags that are pro-eating disorders) it’s refreshing to see headlines that aren’t just showing off this or that fad or harassing celebrities for not looking the same as they once did. I’m choosing to remain optimistic.

Nonfiction titles like What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Fat and You Have the Right to Remain Fat and Unashamed: Musings of a Fat Black Muslim organically make the rounds on #bookstagram and beyond and conversation is stretching past body positivity into the realm of neutrality. Binaries aren’t usually helpful systems as they have no room for nuance and insist on strict adherence to a narrow-minded way of thinking. As it applies to either celebrating body positivity or daily persisting in shrinking oneself through various levels of torture… it seems even worse. Body neutrality then is what we’ve previously glazed over in our rush to fit into one of the above camps so diametrically opposed to the other.

Cheat Day shows one woman’s journey through the completion of a particularly difficult regimen and how deeply the mindset required to do so affects everyone in her life. Tamar Haspel, the Washington Post writer urging us not to so identify with our diets, cautions: “Sure, elevating diet to be part of your identity is bad for discourse. But the reason it’s bad for discourse is that it’s bad for people engaging in the discourse; once you define yourself by your diet, it gets much harder to see evidence clearly…. Once a particular belief gets associated with something you consider essential about yourself — your values, your affiliations, your identity — confirmation bias kicks into high gear, and your chance of figuring out if your one thing is wrong plummets.”

For Kit, the main character of Cheat Day, it’s not just her inability to use hindsight to see how her past with previous dieting didn’t work (she won’t even let her friends and family call them “diets”), but her inability to see anything that’s going on outside of herself. It’s impressive that Kit is so self-aware that she can clue the reader in on how she will inevitably have an affair, for example, because so much else in her life seems so obscured even from herself. The entirety of the book is a slow reveal of who Kit is, leading up to the confrontation she will have to have with herself in order to figure out if that skinny, miserable adulterer is who she wants to be. And I couldn’t get enough. I’m always here for women behaving “badly,” leaning into their impulses and unlikeability. We are all Kit at some point.

There’s plenty more to unpack, much that likely contributed to where Kit finds herself at the beginning of the book. She’s just quit her job working with her sister and cousin at a bakery in Brooklyn. She’s growing resentful of her husband David who seems to constantly be working and who pushes Kit to find a new job or get back to the bakery. Kit predictably goes crawling back to her family’s business and jumps right in to a late shift that will accommodate Matt, a carpenter who has agreed to build new shelves for the kitchen. It’s just as she’s starting to fully commit to her clean eating while she’s usually ravenous she is more satisfied by her tightening torso, that she latches onto her growing confidence in her body and brazenly takes on adultery with Matt.

“Doesn’t an affair start somewhere far behind the action itself?... Matt’s lips were warm and smooth, and the relief of them against my lips, and against my neck, felt exactly how I wanted it to feel. He pressed his hand to my breast. I couldn’t believe what I had: the pleasure of knowing I wanted something, wanted to consume it whole, and just doing so, putting it directly into my mouth. I didn’t feel hungry anymore.”

David the husband is fine. They live in the house she was raised in. They still have sex. They have a cat. She gets along with her in-laws. She’s good at her work. Everything is fine, except nothing is fine because nothing about any of the above placates her or invigorates her in the same way as she does in the middle of or near the end of a diet.

“I blinked and reminded myself how good it would feel later to have drunk only water all day. My skin would be so clear this time next week. Glowing. My stomach flat. In a few weeks, my mind would be razor-sharp, my memory boosted by all the clean blood pumping through my heart. I’d be in control—over my size, my moods, my circadian rhythms—and everyone would admire and envy me for my improved appearance and ironclad willpower. This was the hard part, the days before the results.”

It brings out the worst in her—or does it if it makes her feel so good? No. The constant state of hunger does push her toward some bad decisions, but if leaning into an affair when she feels somewhat abandoned by her workaholic husband is as bad as she gets, then she isn’t even comparable to some of the male leads of countless other literary fictions. And yet, seeing a woman take center stage and own her mistakes as she makes them proves so refreshing as something I didn’t even realize I was looking for in the books I read. Kit is a relative angel to the likes of the narrators in other “bad girl” books like Problems by Jade Sharma, Marriage of a Thousand Lies by SJ Sindu, or the more commercial favorites Gone Girl or Girl on the Train (or any other book from the last decade with “Girl” or “Woman” or “Wife” in the title which more than likely is about a woman who finds out her husband is cheating on her and decides to take moderate-to-murderous reciprocation).

“If I said, “Fuck the Radiant Regimen, let’s quit, let’s cheat,” David would be overjoyed to oblige. I knew this. The friendship David and I felt in the moment—the reminder of our sweet, familiar comfort with each other—could have been extended longer if we stayed out past our usual bedtime. The change in my routine, the late night at the bakery, might bring us some new energy. I could relax about food, he could forget about work. Just for a couple hours, even. We could. We might. It sounded easy. But we didn’t.”

Regardless of cuckolding her husband, or perhaps because of it, in tandem with the honesty and depth of Kit’s emotions and the descriptive details of her past and present, it felt to me that no matter what she did or how unlikeable she is as a character, she also felt too relatable to actually hate. Hers is a life of wanting and Cheat Day is the culmination of what happens when she gets what she thought she always wanted and ultimately realizes that it’s not the “imperfect” body or the stagnant lifestyle that was making her miserable, but herself. Kit is the epitome of “it’s not you it’s me” as she struggles to find balance between the life she has and the one she could have, the food she needs to consume to stay alive and the food she won’t allow herself. Is she going to burn down everything she’s built, modest as she may think it is, or might she see through the haze of hunger and turn herself around before it’s too late?

I wouldn’t fault someone for choosing specific nutritional plans for any reason, but I’m skeptical of any friend who mentions their new diet is just to eat a whole lot less, of everything. There are problems with choosing only moderation that doesn’t rule out anything as long as it isn’t in excess, as well as evidence pointing to the lack of longevity in keeping weight off if you’ve managed to lose some. Guidance is often lacking for the presumed healthy individuals who don’t have to lower their cholesterol, or dial back sugar to reverse pre-diabetes, etc.

Short of hiring a nutritionist who even then might not know enough to cater to what you specifically need to be eating, feeding oneself—a functional necessity to live—can become mired with confusion if you dare to spend too much time on the internet. Everyone has something different to say and that’s usually because they have something to sell. While generally, advice from doctors remains the same: avoid salt, eat more white meat, seek out less processed foods, cook at home more often—their messaging is far outweighed by everything else online. It would leave anyone frustrated. Though, the newness and clear parameters of diet plans that pop up each week could also appeal to people in search of direction. And as Dejan Jotivic of The Guardian speaking about “before and after” photos admonishes, “My difficulty with body transformation photos is that we’re all somebody’s before and somebody else’s after in a system that so brutally values only a narrow margin of physiques. The crowded online environment feeds us an overflowing source of images that reveals to us the body hierarchy…. What’s more, we’re sold universal dreams that grated up to the very real limits of our body - or worse, we decide to push beyond them.”

I’m lucky in that I only dabbled with disordered eating in college. I pushed myself but never pushed myself to the brink. I was complimented for my appearance, for my having lost weight. I relished that praise. I continued to eat restrictively. I don’t remember now what the initial catalyst was or why I stopped. It wasn’t a particularly dark period for me yet the control was nice and my waist was trim. Clothes looked and felt good wrapped around it. It was what I’d always wanted but it didn’t make me feel any of the positivity and excitement I heard in the voices behind the compliments laid upon me. I was left feeling empty and not just because my stomach was so rarely full.

Years before, I was a gymnast. I genuinely enjoyed the sport as a way to exercise and push my own flexibility and general endurance. When I joined my high school’s team and starting practicing every day instead of twice a week at my club gym, I promptly dropped about 20 pounds. Everyone noticed. My face slimmed out and the conditioning that was part of my training became a little easier. I could swing around the uneven bars more smoothly, finally able to consistently nail the front hip circle I’d been trying to master. I was never Olympic-bound but I got so much joy out of the few cool tricks I could do.

Both in high school and college, dropping weight for me was viewed as a victory to the people around me. Only did the accidental weight loss in high school actually feel in any way satisfactory. And it wasn’t because I could buy new jeans in a smaller size. I was getting stronger, not purposefully shrinking because I thought being fat was bad—even though that is 100% the messaging I received as a young woman nearly every day. Today my body is my own again. It’s still strong in places I like to have extra muscle, in my thighs and upper arms, and it’s also more round and soft all over. I learned how to cook properly throughout the pandemic and I eat whatever I want. I consider portion sizes and sodium or sugar levels but I won’t go back to the deprivation tactics I once used against my body.

There’s no point in trying to morph my shape into one I cannot sustain. And there’s certainly no point in allowing my insecurities or the warped opinions of society to manipulate me into thinking that I have to look one type of way. Being thin never made me into a better person, and being fat doesn’t make me worse or stupid or wrong in any way. I just am. Like Kit I had to go through the sliding scale that was my weight as a teen and a twenty-something in order to identify what good health means. I also had to determine if I’d let one aspect of myself dominate my whole life and personality, or if I could be content with the person I am and always was.

Cheat Day

By Liv Stratman

320 pages. 2021.

Buy it now from our Bookshop in the US.

Keonhacai hôm nay cập nhật tỷ lệ kèo nhà cái , chuẩn, nhanh, kèo bóng đá trực tuyến, kèo châu Á, châu Âu, tài xỉu từ nhiều giải đấu lớn nhỏ.

188bet là cổng cá cược hàng đầu với kho game đa dạng, từ thể thao, casino đến game bài. Giao diện dễ dùng, bảo mật cao, khuyến mãi hấp dẫn, mang đến trải nghiệm an toàn, mượt mà. https://188bet.academy/

tỷ lệ kèo nhà cái – cập nhật nhanh chóng kèo bóng đá từ các nhà cái hàng đầu, hỗ trợ soi kèo chính xác, phù hợp cho cả người mới lẫn dân chơi chuyên nghiệp.

kubet – nhà cái cá cược trực tuyến uy tín, giao dịch siêu tốc, bảo mật, hỗ trợ 24/7. kubet casino – giải trí đẳng cấp, nhiều game, nạp rút minh bạch.

vb88 là sân chơi cá cược trực tuyến uy tín, thu hút đông đảo người chơi với các sản phẩm thể thao, mini game hấp dẫn. https://vb88.live/